What am I up to now?

February 18, 2026

June, 2021

This time last year, everyone was talking about Covid testing. Vaccines seemed years away and rapid, cheap, accurate tests were the solution. However, in the US, new tests were left in regulatory purgatory: as early as June 2020, companies were offering cheap, paper-strip tests which produced results in 15 minutes. One of these tests, the Abott test, was eventually made available in late autumn (with a prescription) with reported accuracy above 90%.95.0% sensitivity and 97.9% specificity, for you epi nerds.

I had my own run-in with medical testing recently. In April, I came down with a bad stomach bug. After a blood draw and a few hours wait at a local clinic, I was told I had typhoid and sent on my way. This diagnosis came by way of a Widal test, an antibody test developed in 1896!!! , years before biologists had an understanding of antibodies in immune responses.Witebsky, 1954 This, somehow, is the state-of-the-art in typhoid diagnosis.

The Widal test has a lower specificity and sensitivity than the Covid tests which were never approved for use in the US. The headline is Widal’s specificity: 18%Mawazo, Bwire, and Matee, 2019 of people who don’t have typhoid correctly test negative.Compare this to 98% specificity for the at-home Covid Abbott test discussed above, which was designed in just three months. If 100 perfectly health people took the Widal test, 82 of them would test positive for typhoid.

I definitely wasn’t perfectly healthy, and because I didn’t have a blood or stool culture done, there’s no way to know if my Widal result was a true or false positive. Instead of typhoid, I may have had any of a dozen other diseases floating around Freetown.When telling my German friends in Freetown why I couldn’t play water polo that week, I learned that, in German, typhus

means both typhoid and typhus. Despite being different diseases with separate vectors (food and fleas, respectively), symptoms, and treatments, German doesn’t distinguish the two.

For Covid, fast and scalable tests were more important than high specificity.Larremore et al., 2020 (preprint) In mid-2020, low specificity would have made people overly cautious, but would not have put containment efforts at risk. Over-diagnosing typhoid, however, is a problem. The go-to treatment is a ten-day course of antibiotics. Because the primary diagnostic tool is almost useless at identifying patients without typhoid, antibiotics are vastly over-prescribed.

I tend to be skeptical of the doomsday case of anti-microbial resistance (AMR).My hot-take: after colony collapse, AMR is the most over-hyped extinction risk. But over-prescription has some effect: the WHO claims that, as of 2016, “more than 200 000 newborns die each year from infections that do not respond to available drugs.” Another forecast estimated that AMR could cause more deaths than cancer in 2050.The Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2014

Unlike Covid tests, the low specificity of the Widal test has potential longterm consequences. Typhoid infects tens of millions of people every year, and antibiotics are over-prescribed in Africa and south Asia. As a local friend put it, “Doctors here treat everyone for malaria or typhoid, unless they’ve got a broken leg. And even then, antibiotics can’t hurt…” A diagnostic tool that’s better than even would make a difference.

Contents

Reading

Along with my Kindle, I brought three books with me to Freetown: Whitman’s “Leaves of Grass,” FitzGerald’s “Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyam,” and “Open Borders.” The last, a work of graphic non-fiction,An unfortunate name for the genre, I think. is only available in paperback. It’s one of those books I bought knowing that I’d agree with every page, but read closely anyway. Bryan Caplan provided the economics and Zach Weinersmith provided the illustrations (including delightful caricatures of Michael Clemens and George Borjas). The format makes it difficult to excerpt but easy to enjoy.

As for the other two books, I’ve never been able too bring myself to read poetry on a laptop or e-reader. For long poems, there’s something visceral about turning a paper page that maintains the flow of the verse which tapping a Kindle screen can’t replicate. For anthologies of short poems, like the Rubáiyát, the serendipity of stumbling upon any poem in particular is replaced by a linear progression through the four-line enigmas. There’s no “random page” button on a Kindle.

Besides these three books, everything else I’ve read since arriving has been electronic.

Decadence

Some books are classics despite their length; others are classics because of it. Gibbons’ “The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” is in the second category. I haven’t read it, and I don’t plan to, but the six-volume work has fascinated me from a distance. And while I haven’t read the book, I did read Alvaro de Menard’s 25,000 word review.

“Decline and Fall” is both literary and academic. The language is important: Menard calls it “monumental, active, Latinate, flamboyant, often epigrammatic.” It’s fun to read someone who’s so good at putting sentences together:

Gibbon’s sentences are long and balanced; his thought is dualistic and symmetrical, often based on comparisons or parallels between actions, characters, wars, and ages. He loves to expose contradictions within characters: Augustus is “at first the enemy, and at last the father” of Rome. He often goes for striking antitheses and juxtapositions, methods which allow him to instruct, pass judgment, and most importantly display the decline of the empire: he plays the old against the new, the particular against the general, the ideal against the pragmatic.

But epic language only matches epic events. Spectacle is what makes “Decline and Fall” what it is: the word recurs throughout Menard’s review, and Borges’ as well.

A decadent empire requires decadent emperors. But Gibbons isn’t given to psychoanalysis. The closest we get to Gibbons’ characters is through his dunks:

[Julian] was assisted by the eloquent Mamertinus, one of the consuls elect, whose merit is loudly celebrated by the doubtful evidence of his own applause.

Or:

[On the historian Gregory of Tours] His style is equally devoid of elegance and simplicity. In a conspicuous station he still remained a stranger to his own age and country; and in a prolix work (the five last books contain ten years) he has omitted almost everything that posterity desires to learn. I have tediously acquired, by a painful perusal, the right of pronouncing this unfavourable sentence.

Gibbons’ focus on Roman decadence doesn’t give him an opportunity to focus on the Good Emperors. Maugarite Yourcenar’s “Memoirs of Hadrian”, which I was reading at the same time, scratched that itch.

What was Yourcenar’s theory of the Good Emperor Hadrian? In his own words, “my greatest asset of all was perfect health: a forced march of twenty leagues was nothing; a night without sleep was no more than a chance to think in peace. Few men enjoy prolonged travel; it disrupts all habit and endlessly jolts each prejudice.” Ezra Klein said somewhere that one of the most important skills for a modern CEO was the ability to get restful sleep on an international flight. A certain type of endurance enables swift governance, and Hadrian spent more time away from Rome than any peacetime Emperor in history. He continued his travels almost until his death.

Yourcenar’s Hadrian is a fascinating character; one reviewer called him “the best man ever written by a woman.” The book moves as quickly as the Emperor, but toward a different purpose. Hadrian thinks he is building his empire to be “an admirable idea, a splendid impulse of the soul.” Yourcenar knows it’s just a dream. Decadence is inevitable and imminent.

A year or two ago, I couldn’t define “decadent” past a slice of chocolate cake. If pressed, I might have made a connection to the baroque, but the “luxury” part of the definition was more salient than the “decline” part. Ross Douthat is mostly responsible for the resurgence of the word, but Thiel and Cowen’s great stagnation (now over?) should receive some credit as well.

“Decline and Fall” is the defining work of decadence. Gibbons was obsessed with the idea, and not just in Rome: he and Burke commiserated as the Bourbons fell, and Gibbons feared the American Revolution presaged a similar disaster in Britain. Eric Ambler’s opinion was that, “in a dying civilization, political prestige is the reward not of the shrewdest diagnostician but of the man with the best bedside manner.” Prætorians have this bedside matter, so did William Pitt the Younger. Hadrian did not.

But as hard as I look, I don’t see any of Gibbon’s decadence in Douthat’s and Thiel’s complaints about America today. Here’s a fun and representative listicle, “Ten ways we are decadent.” My summary:

- 1. “Go into a room and subtract off all the screens. How do you then know you’re not in 1973?”

- 2. Falling birth rates

- 3. Culture — movies remakes are increasing

- 4. IQ is falling, reverse Flynn effect

- 5. Labor productivity has stalled

- 6. Growth is underperfomring since 2008

- 7. Growth of populism

- 8. Death of middle class jobs

- 9. Housing is too expensive

- 10. Culture — books and authors are boring and homogeneous

My thesis is that this is a list of conservative decadence: “Furniture from the 1970s, music from the 1980s, clothes from the 1990s. And let’s not forget the current interest in horoscopes.” Stagnation is not decadence; Thiel and Cowen can divorce those cataclysms. To Gibbons, the good emperors were the conservatives. Decadence, instead, was moving too fast and was too uncontrollable. Today, conservative stagnation might be preferable to radical decadence. We have much further to fall today than Rome did.

Non-decadent books

On my second read, “Persuasion” is still my favorite Jane Austen novel. That said, I picked it up again expecting more value from the more mature charactersRelative to Pride and Prejudice

or Emma

, my sister’s favorite. than I found at 18 years old. The maturity arrived; the value didn’t. I probably enjoyed “Persuasion” more in high school because of my since-faded familiarity with the Napoleonic wars. Wentworth made more sense in that context.

The short stories in Egan’s collection “Axiomatic” punch you in the face, over and over again. Ted Chiang is the only modern science fiction anthologist in his league, but Egan’s science is much “harder” and his fiction is much more personal. Even the economics in the story are rewarding — American health insurance is a key plot element in two stories. I was reminded more of The Twilight Zone than Black Mirror in tone, but not for lack of trying.

The stories are also the most deeply conservative new-wave science-fiction I’ve read, in a G.A. Cohen sense. An intuition of disgust runs behind many of Egan’s stories. The future is going to be weird; if it weren’t weird, it would be the present. Egan’s futures make that weirdness repugnant, in the ways that we change our bodies, our relationships, our minds.

When a mouse found it’s way under my bednet last week, I fondly remembered Martha Gelhorn’s “Travels with Myself and Another”:

I should say at once and get it over with that I hate mosquito nets, both for themselves and for what they imply. And dread wriggling myself somehow inside and somehow tucked in and then, hot and stifled, realizing, in the dark, that something else is in with me—what?—a spider, an unknown flying or crawling insect, the insomnia-making mosquito? That’s my first and last report on mosquito nets; otherwise I’d talk of them daily.

The “another” in the title is her then-husband, Ernest Hemingway, referred to as U.C.For Unnamed Companion.

throughout the book, Ernest Hemingway. The book is enjoyable, skimmable, and witty. Maybe too witty: the marriage was entirely based on banter. Upon seeing another American on a train in Guandong during the Chinese Civil War:

I made a bet with U.C. “Bet you twenty dollars Chinese he comes from St Louis.”

“Why?”

“I think it’s a law. When you get to the worst farthest places, the stranger has come from St Louis.”

“Done.”

I moved along the unsteady train until I saw the man, reading alone in his cindery compartment. I asked if he was American. Yes. Did he come from St Louis? He looked only slightly surprised and said Yes. I said thank you and left and collected twenty Chinese dollars.

U.C. thought about that. Hours later he said, “Maybe it’s something you catch from the water. Maybe it’s not your fault.” Since I too come from St Louis.

Gelhorn’s aphorisms stand alone, as well:

The night took on the most unpleasant quality of nights which is to be long.

Feel free to skip the chapters on Africa and Israel; pay special attention the Caribbean.

I often wonder why, if traveling is so worthwhile, travel writing is almost invariably dull. Maybe travel is too visceral: people often start stories about Bombay or Berlin or Botswana which inevitably trail off to, “I guess you just had to be there.” Gelhorn thinks this is bullshit, her weakness is that she can’t convey enough of the details.

The trouble is that experience is useless without memory. Serious travel writers not only see and understand everything around them but command erudite cross references to history, literature and related travels. I couldn’t even remember where I’d been. I think I was born with a weak memory as one can be born with a weak heart or weak ankles. I forget places, people, events, and books as fast as I read them. All the magnificent scenery, the greatest joy of travel, blurs. As to dates—what year? What month?—the situation is hopeless. I am still waiting for the promised time, said to arrive with advancing age, when you forget what you ate for breakfast but the past becomes brilliantly clear, like a personal son et lumière.

“Foragers, Farmers, and Fossil Fuels” is a series of lectures by Ian Morris, presented with comments by Richard Seaford, Jonathan D. Spence, Christine Korsgaard, and Margaret Atwood. Morris’ thesis, which brought such esteemed criticism, is that a society’s method of energy capture determines its moral values. An archeologist and historian, Morris’ foray into the history of moral philosophy was enjoyable but not nuanced. He summarizes his arguments for the three titular sets of values as:

- 1. Foragers tend to value equality over most kinds of hierarchy and are quite tolerant of violence.

- 2. Farmers tend to value hierarchy over equality and are less tolerant of violence.

- 3. Fossil-fuel users tend to value equality of most kinds over hierarchy and to be very intolerant of violence.

The format was the most fun and important part of this read. Morris introduced his argument in four essays, then each commentator engaged him in a dialogue of shorter essays. As a way to present lectures, this was much more enjoyable than video or slides.

Listening

Works in Progress recently featured an essay by Ryan Murphy on “peak culture.” Murphy argues that newer culture, “film, art, music, and literature”, is better culture.

How do we know this means that the modern world is better? Because people don’t just copy and paste. All of these incredible works of the past are just sitting there waiting for you to enjoy them (with 80% or more of the impact of experiencing the original in real life) on YouTube, your local library, or Google Images. Instead, we choose to experience other things. Economists have a phrase for this: revealed preference. Our revealed preferences mean something, and it ought to be a baseline assumption, if nothing else, that if we are making the choice for one thing over another it’s because it’s better for us. To recapitulate: in a given field of art or practice, if we can replicate a near approximation of a historical masterwork at a cost no higher than it was in the past, and we’re doing something else, that something else is probably better than the supposed historical masterwork.

I mostly read old books, and so do a lot of people, so an argument from revealed preferences in literature doesn’t convince me. But I listen to plenty of new music, and Murphy’s “near approximation” thesis proves too much. We can approximate Bach or Allauddin Khan today, and we do.

Today’s music couldn’t have been produced even a few decades ago.

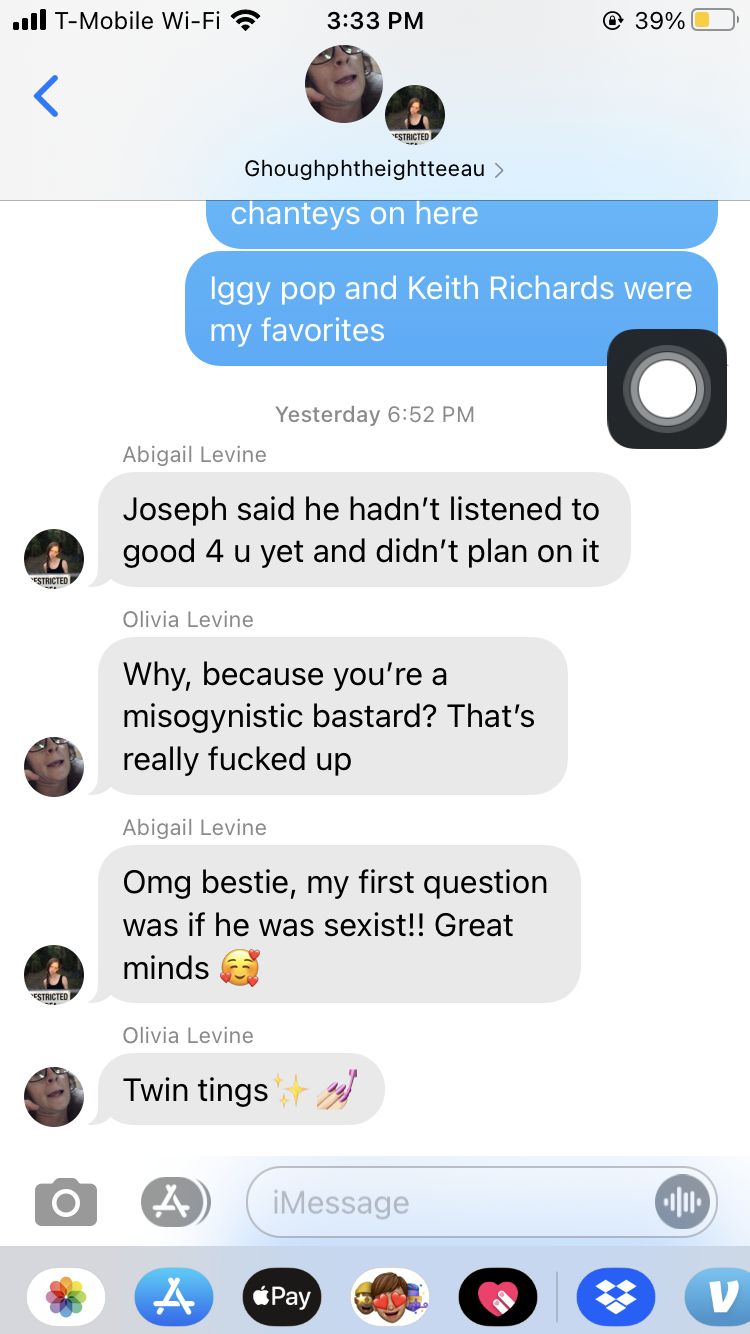

My sisters were roasting me for not having listened to Olivia Rodrigo’s “Good 4 You.” So, as I do a few times a year, I went and listened to the US Top 50 playlist on Spotify. Only four of the songsGood 4 You,

Heat Waves,

Blinding Lights,

and Forever After All.

Even Forever After All

, though, is solidly 2010s pop country music, and only included because of Luke Combs’ style. sounded even remotely like anything I’ve heard from before 2000. Of the fifty songs, only the purposefully lo-fi songs like Billie Eilish and Olivia Rodrigo’s acoustic versions could have been approximated before the 1970s.

In response to Murphy, more than just changes in technical ability, I would point out the music doesn’t optimize for “better.” Spotify pays musicians per song streamed, and predictably albums today include more, shorter songs than a decade ago. The music industry also optimizes for “new.” An equivalent Top 50 list from 1821 would have pieces on it from years or decades prior, but approximately no one is going to be listening “Levitating (feat. Da Baby)”Currently #8 and admittedly a top-notch pop song. in five years.

To be fair to Murphy, he mostly leaves music alone and focuses on film. But if we try to identify the better era of music based on revealed preferences, this theory would have to confront the changing *role *of music. Olivia Rodgrigo doesn’t replace Beethoven; the people who went to the symphony in the 19th century are very similar to symphony goers today. Pop music replaces folk musicIn the sense Ted Gioia uses. , and even that role is changing.

In the vein of work songs, I enjoyed the album “Son of Rogues Gallery” this month. The subtitle is “Pirate Ballads, Sea Songs, and Chanteys,” and the “Various Artists” credited are impressive. An early surprise was Keith Richards grumbling about the Shenandoah, as far from a sea song as you can imagine but it fits quite well. Other highlights include a funky chantey sung presented by Macy GrayOf I Try

fame. , “Off to Sea Once More,” and Iggy Pop singing of an admiral with a magic butthhole.

Here are some other albums I listened to for the first time this month. I really enjoyed each one; if this makes you think of any recommendations, please send them along!

- Live in Calcutta, Debashish Bhattacharya

- The Dreams and Prayers of Isaac the Blind, Osvaldo Golijov **

- Será, La Vida Bohème

- Heart and Soul, Sonny Black

- Soundtrack to Jane Eyre, Dario Marianelli

- Eddie, Busty and the Bass

Writing

I wrote more this month than any month since university. All of it is now under client or peer review, but I’m looking forward to sharing drafts of two or three working papers in the next six weeks:

- 1. A draft of a paper bounding the long reflection, as outlined by Ord (2020) and MacAskill (2018);

- 2. A working paper analyzing the effects of natural resource discoveries on autocratic attitudes and coups (to be presented at APSA 2021 in Seattle);

- 3. A preliminary draft presenting findings on "charter cities as emigration reduction policy."

If any of these sound especially interesting, please reach out!

Eating

Whenever I was sick as a kid, my parents would bring home wonton soup from the closest Chinese food restaurant. It was hot, salty, and filling enough for an elementary school kid with strep throat. I haven’t found any Americanized Chinese food in Freetown; the restaurants here largely serve the Chinese expat community and are therefore “authentic.”For reference to DC readers, the two Chinese food restaurants here would fit better in Rockville or Fairfax than Bethesda or McLean. This authenticity manifests itself on iPad menus with more than 500 dishes and a request that all orders be placed at once.

While I was down with typhoid, I couldn’t even have stomached wonton soup for the first couple of days. By the time I was feeling peckish again, a French friend had taken pity on me and dropped off several packs of his favorite instant ramen, Pho’nomenal. These were so good. They were also, apparently, contraband. When I had recovered, I tried to return the favor with a six-pack of the noodles. However, none of the expat grocery stores carried the brand, and no companies are even licensed to import them. My French buddy’s girlfriend knows a guy who keeps them behind the counter of his shop. There’s no way to know if the antibiotics helped me recover from typhoid, but illegal noodles definitely did.