What am I up to now?

February 18, 2026

September, 2021

I don’t really know what’s going on in Afghanistan. Having visited twice, I’m the go-to expert for questions from grandparents, uncles, and family friends. I don’t mind; I’m happy to share my experiences, even if I can’t provide any insight into gepolitics.I’ve got a pretty good slide show, too. Despite this, I’d like to put my ignorance on the record.

Most of my time in the country was spent in the Panjshir valley, now the only region not under Taliban control. Any resistance—organized or not—against the new regime will be organized or supplied from this small province north of Kabul.2021-09-08: this became wrong faster than I expected. The valley has played host to human conflict for at least the whole period covered in my high school history classes.

Panjshiri traffic cone.Alexander the Great passed through on his way to and from India, and Tamerlane camped in the field where the provincial football stadium now stands. Along the main highway, kids have turned burned-out Russian tanks into playgrounds; the tailcones of MiG-dropped gravity bombs are used as traffic cones. And there are so many discarded artillery shells from various occupiers that Panjshiris use them in construction.

The support beams in the roof are disarmed tank shells, leftover from the Soviet invasion.

If there’s one thing I’ve gained from the disaster of the past month, it’s a realistic view of what social scientists can and can’t do. Nation building, as a project, failed. This was not for a shortage of expertise. The Pentagon was focused on shoring up Afghan capabilities as early as 2004, and brought in academics and subject matter experts to make a plan. I’ve met dozens of members of the Provincial Reconstruction Teams; each one was a smart, dedicated person who believed they were going to leave their corner of Afghanistan stronger than they found it. The expertise wasn’t limited to the Americans: former President Ashraf Ghani had a PhD from Columbia and co-authored a book called “Fixing Failed States.” Despite mountains of diplomas and years of resiliency conferences, Afghanistan crumbled over one weekend.

That’s what we can’t do. What can we do?

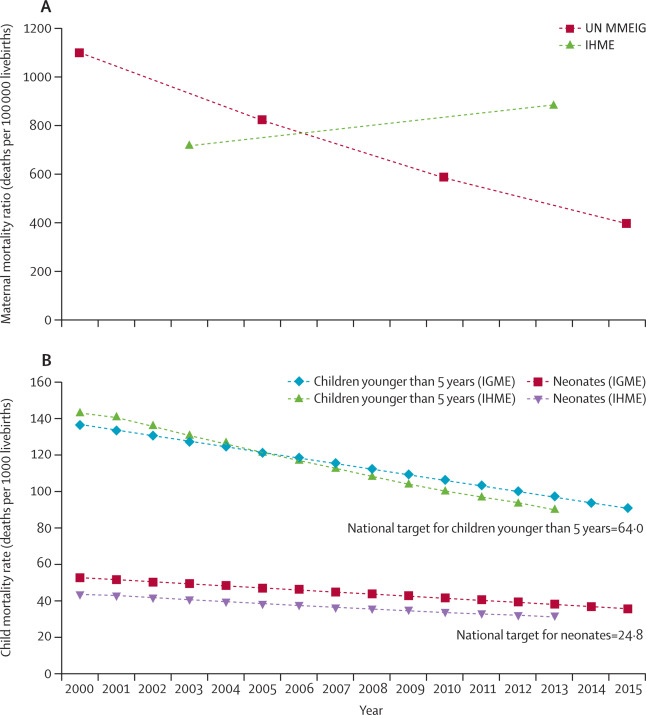

The US occupation doesn’t deserve credit for this as much as the pre-2001 Taliban government deserves blame. There was so much low-hanging fruit that progress was inevitable once international aid started to flow into Afghanistan. But if aid is cut off and international organizations pull out once again, these trends could head in the wrong direction.

Justin Sandfeur of CGD commented, “we don’t know how to build nations. We do know how to reduce infant and maternal mortality.” This gets to the heart of what could go wrong. Afghans under the Taliban are worse off: they will die younger, their children will be sicker, and they will have less agency over their own lives.

Contents

Reading

To start on the Afghan theme, I’ll include one of my old favorites. After my friend John Gerlaugh invited me on the first trip to Panjshir in 2017, I picked up “A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush,”Referenced in the title of this excellent and important graph from The Economist. Eric Newby’s 1950s travel book about a London clothes salesman (Newby) and a diplomatic friend attempting to climb Mir Samir, the highest unclimbed peak in the Panjshir. As neither had never before attempted to climb anything taller than a stepstool, they fail, repeatedly and hilariously. Evelyn Waugh describes the book as “intensely English,” and, sure, the confidence had to come from somewhere. If it’s any consolation, Mir Samir has only been summited once since, despite dozens of attempts. This is as close as I ever got:

As I mentioned a couple of months ago, I do all of my reading in Sierra Leone on my Kindle. The days when a year of field research means “little or no access to books” are gone, thanks to epubs and mobis. Unfortunately, not all books are available as as ebooks. So I took advantage of the only permanent address I have, and ordered a couple dozen books to my parents house in Maryland. Here are some of the highlights I brought back to Freetown with me.

The first book I picked up after arriving home was James Scott’s “The Moral Economy of the Peasant,” based on his fieldwork in Southeast Asia. I don’t know how it happened, but my Twitter bubble has fully embraced Scott the anarchist; it often feels like every sixth tweet is about “the art of not being governed” or “legibility.”Connecting Scott and Afghanistan is this excellent essay by Anatol Lieven on Yaghistan and the impossibility of governing Pashtuns. HT to James Crabtree. Instead of starting with the classic “Seeing Like a State,” “Moral Economy” is more relevant to my current research in Sierra Leone. This was the first book which has captured my intuitions of our duty towards subsistence farmers. Scott focuses on explotaition, not as a positive or a negative, but as fundamental to the moral economy as the concept of markets. The book fails as a self-described work of “Marxist anthropology,” because it actually makes sense.Apologies to any Marxist anthropologists readers.

For a similar reason, I picked up “The Economic Theory of Agrarian Institutions,” an edited volume from the 1980s which confused me, because I didn’t know that development economists were allowed to do theory. I’ve read Joseph Stiglitz’s introductory essay three times now, and found something new each return. Stiglitz repeatedly reminds the reader that subsistence farmers are rational, whacking you over the head with examples. The recommendation came from Marc Bellemare, who wrote elsewhere, “whenever you find yourself thinking that some behavior you observe in a developing country is stupid, think again.”

I also brought back Parfit’s “Reasons and Persons.” I’ve read the opening sentenceLike my cat, I often simply do what I want to do.

Parfit, the subject of my favorite New Yorker profile, did not in fact own a cat, nor did he want to. But he liked the sound of this sentence so much that he signed an agreement with his sister to take legal, but not practical, possession of her cat. at least a dozen times, and the first hundred pages three times. But I’ve never been able too crack any deeper on my Kindle or computer screen.

This is because Parfit stores axioms and thought experiments like variables and functions in a massive DO file. Parfit will define claim S10I can rationally ignore desires that are not mine.

and posit argument P5I can rationally now ignore desires that are not mine now.

, so he can write ten pages later that, “according to the Appeal to Full Relativity, if we accept (S10) we should also accept (P5). Since an S-Theorist must accept (S10), but cannot accept (P5), he must reject the Appeal to Full Relativity.” This would be easy to follow on a computer screen if moral philosophy were written like code. It’s not, though, and having a hard copy is my only hope. After two weeks, I’m further along than I’ve ever been before,Up to Simple Teletransportation and the Branch-Line Case

, which pulls off the rare argument-from-Star-Trek quite well. and enjoying it.

Matt Clancy recently ran the first ever EconTwitter science fiction book club, inspiring me to read Vernor Vinge’s “A Deepness in the Sky.” Vinge’s work on technological forecasting, less well known, is also very impressive. Fitting with Clancy’s research focus, “Deepness” is a tremendous work of public and innovation economics. By introducing sci-fi physical constraints, Vinge plays with various models for how governments can push fundamental science forward (or, more often than not, fail).

Another fun sci-fi economics book was “The City in the Middle of the Night” by Charlie Jane Anders. The economy in Anders’ book uses different currencies for each type of good you might want to purchase, which Noah Smith (who consulted on the novel) calls an “utterly insane system.” The book also takes place within my favorite astrodynamic phenomena, a tidally locked planet (or “eyeball earth”). With one side of the planet perpetually scorched and the other perpetually frozen, life can only exist in a twilight band where the two meet.

For the flight back, I carried “Whereabouts: Notes on Being a Foreigner” and Jhumpa Lahiri’s “The Clothing of Books.” One of my reading goals for the year is to read every word Lahiri has ever published, and it’s been a fantastic decision so far.

As a postscript, it was good to read in my parents’ home again. My sisters were there for the whole month, and my reading habits have always bothered them slightly. Not so much what or when I read, but how: I tend to take up far too much space on the couch; I fidget (flicking or folding pages, or flipping the cover of my Kindle); I laugh when I’m amused or gasp when I’m surprised. When I was in high school, I probably enjoyed annoying them. Now, reading near people I love enjoys me the book more. Anne Enright, in an interview in the NYT, captured the feeling well.

Describe your ideal reading experience.

I like being alone in the center of family. I think this is the way I read as a child, surrounded and private at the same time. I like to feel privileged by the secret contents of the book.

Listening

In July and August, I took Ted Gioia’s One Hundred Best Albums of 2020 and listened to a random pick (almost) everyday.

The only one I regretted listening to was the soundtrack to “Color Out of Space”, a 2019 horror movie about a Lovecraftian meteor. I have always followed the Munroe school of thought regarding horror movies, and have now learned that this extends to their soundtracks. The highest compliment I can give is “effective.”

The album I returned to most frequently was Lyra Pramuk’s “Fountain”. Weird, something hidden. I’m still trying to figure it out.

Also excellent, with broad appeal: Georgie Sweet’s “Misunderstood” and Shabaka and the Ancestors’ “We Are Sent Here by History.” Shabaka Hutchings on various wind instruments, backed by Ariel Zamonsky on bass, makes this one of my favorite popular jazz albums. I didn’t get the afrofuturist vibe which some reviewers called out; too much fatalism. Start with “The Coming of the Strange Ones.”

The album which I recommended to the most friends (which of course says more about my friends than the quality of the music) is Dirty Projectors “5EPs.”

The overall winner, however, has to be The Westerlies’ “Wherein Lies the Good.” This is a magical record and the “Entropy” suite which concludes the track listing might be my most-listened to track of 2021.

Finally, being within a three-hour time difference of San Francisco, I was able to listen to many more Giant’s games than from Freetown. I was too young to remember, but Jon Miller was the first voice of baseball I heard. Miller broadcast Orioles games until 1997, when he moved to San Francisco. I’ve listened to him call games from Scotland, Afghanistan, Kolkata, and Sierra Leone.

I remember one Miller anecdote particularly well. During the 2012 Giants World Series run, my high school English teacher had assigned “Macbeth,” which I completely refused to read until the night before the test. The game that night started around 10pm on the East coast, and as I was speedreading through Act 2, Pablo Sandoval stole his first and only base of the year. Miller’s call:

And let us not be dainty of leave-taking

But shift away. There’s warrant in that theft

Which steals itself when there’s no mercy left.

It’s jarring to hear iambic pentameter on a sportscast. I was only confused for another two pages, however. At the end of Scene 3, Malcom recited the same lines!

Writing

I’m circulating a draft of my paper on the long reflection; if this sounds interesting to you, let me know and I’ll send it along. I’ve got two other working papers on political economy up on my research page; I’m scheduled to present both of these at APSA 2021 in Seattle.

Eating

Bagels.