What am I up to now?

March 2, 2026

October, 2022

Metrics, micro, macro. Measures, minimizers, magnitudes. Marshallian methods must mock my motivation. Matrices, μ, monotonicity; Malmqvist models mirth myopically? Moreover, myself maybe made mad, meaning “mental”, mastering much minutiae modeling mankind’s many monetary market messes.

(The first month of economics grad school is going great. Let’s dive in.)

Contents

Reading

A Suitable Boy

I’ve done less re-reading of fiction this year than I usually do. In fact, I’ve been positively smug about how much new fiction I’ve exposed myself to this year.I’m writing this a few days after the Ernaux win (I lost about £30 on the betting markets, I had money on Murnane and Edna O’Brien). I’d never heard of Ernaux before reading through the contenders sheet last week; I doubt I’ll read her but only because I have an inexplicable aversion to autofiction. Earlier this month, however, I returned to one of my old favorites, Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy. Seth wrote the bookI read it on kindle the first time, and was astounded to see the size of a hard copy, more than 1,100 pages! It read so fast while I was in Sierra Leone, about a week. Just now, I sprinted through in twelve days, but that felt like quite an achievement. instead of studying during his economics PhD at Stanford; he’s joked that it took him “eleven years not to finish my PhD.” I’m heartened to know I have a novelist/poet career to fall back on if the economics thing doesn’t work out.

The novel is about a 19-year-old woman, Lata, being pushed towards marriage by her mother in the 1950s; Lata’s choice comes down to three boys of varying suitability: Kabir, Haresh, and Amit. Much of the romantic story takes place in Kolkata, but action branches to Delhi, Lucknow, and Bihar. The scope of the novel led to overly confusing comparisons to War and Peace; Nehru shows up often, and the resignation of Rafi Ahmed Kidwai is covered in detail.

Unlike Tolstoy, however, Seth’s eye for the political scope is without pretension. His biographizing of Nehru is deeply sympathetic personally but caustic historically. There’s a delightful critique of Tolstoy’s “masses” theory of history; agree that history is contingent, it’s not the decisive action of the Great Men which decides events. But instead of the sum of infinitesimals which is a mass movement, what matters are the unknowable quirks of individuals making decisions.C.f., JFK misunderstanding what the Joint Chiefs meant when they told him the Bay of Pigs had a ‘fair chance’ of success. If only they’d read Superforecasting. Seth’s portraits of early Indian leadership fits in this school, staunchly against Tolstoyian contingency, but with deep sympathy for it.

The actual question of interest, much more central than for Natasha, is who is most suitable for Lata? In my memory, before beginning my re-read, Amit was the only choice. I might have had a crush on him myself, and Seth draws him almost as a self-portrait — an Oxonian poet and novelist, already acclaimed in the West and Anglophone India, Amit is superlatively sympathetic.The most illustrative bits about him are massive spoilers, so I’ve put one of my favorite at the bottom; search for ‘Chatterji.’ But there’s also the deeply romantic potential of the bad-boy Kabir; being Muslim, his presence causes Lata’s mother no end of stress. And Haresh is hardworking and simply adoring of Lata. Tho he starts pathetic, he grows on me the most throughout. At one point, on a train, he makes a list entitled “My Life:”Moreso than planes or buses, trains inspire lists with grandiose titles.

1. Must catch up with news and world affairs. Haresh felt he had not come off well on this account during his meetings with the Mehras. But his work kept him so busy that sometimes he hardly had time even to glance at the papers.

2. Exercise: at least 15 minutes each morning. How to find the time?Ha.

3. Make 1951 the deciding year of my life.

4. Pay off debts to Umesh Uncle in full.

5. Learn to control temper. Must learn to suffer fools, gladly or not.

6. Get brogue scheme with Kedarnath Tandon in Brahmpur working properly. This he later crossed out and transferred to the work-related list.

7. Moustache? This he crossed out, and then rewrote together with the question mark.

8. Learn from good people, like Babaram.

9. Finish reading major novels of T.H.Thomas Hardy. This is likely the most autobiographical item on Seth’s list.

10. Try to keep my diary regularly as before.Who hasn’t written this in a diary before?

11. Make notes of my five best and five worst qualities. Conserve latter and eradicate former.

Haresh read over this last sentence, looked surprised, and corrected it.

A Suitable Boy is only slightly an economic novel, but it is an economical one. Seth’s aversion to adverbs is second only to Stephen King’s. When he does deploy them, it’s done mockingly.

The talkative [guppi] was asking Maan about his love life, and Maan was attempting weakly to fend off the questions. “People’s love lives are not very interesting,” said Maan, sounding unconvincing even to himself.

“How can you say that?” said the guppi. “Every man’s love life is interesting. If he doesn’t have one, that’s interesting. If he has one, that’s interesting. And if he has two, that’s twice as interesting.” He laughed delightedly at his sally.

Another reason I’m partial to Seth is our similar taste in Shakespeare: Twelfth Night, my favorite of the comedies, plays an extended role in the plot. Lata is cast as Olivia;'’The girl who played Viola too was excellent, and Lata enjoyed falling in love with her.’’ one of her suitorsThe Muslim boy disapproved of by Mrs. Mehra. is a talented, pathetic Malvolio. The version staged in the book, “Indian-movie-style, concluded with the last of four songs.” And contemplating her niece prior to opening night:

Sometimes, sitting here, with the marked script of Twelfth Night open on her lap, Lata substituted the word “happiness” for “greatness” in the famous quotation.‘Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.’ She wondered what one could do to be born happy, to achieve happiness, or to have it thrust on one. The baby, she thought, had arranged to be born happy; she was placid, and had as good a chance as anyone of happiness in this world, her father’s poor health notwithstanding.

I’ll throw in a long section, my favorite, to conclude. Amit is giving a seminar about his new novel to high society in Kolkata:

“Do you believe in the virtue of compression?” asked a determined academic lady.

“Well, yes,” said Amit warily. The lady was rather fat.

“Why, then, is it rumoured that your forthcoming novel — to be set, I understand, in Bengal — is to be so long? More than a thousand pages!” she exclaimed reproachfully, as if he were personally responsible for the nervous exhaustion of some future dissertationist.

“Oh, I don’t know how it grew to be so long,” said Amit. “I’m very undisciplined. But I too hate long booksQuite self-aware, from a novelist on page ~900 of 1,100. : the better, the worse. If they’re bad, they merely make me pant with the effort of holding them up for a few minutes. But if they’re good, I turn into a social moron for days, refusing to go out of my room, scowling and growling at interruptions, ignoring weddings and funerals, and making enemies out of friends. I still bear the scars of Middlemarch.”

“How about Proust?” asked a distracted-looking lady, who had begun knitting the moment the poems stopped. Amit was surprised that anyone read Proust in Brahmpur. He had begun to feel rather happy, as if he had breathed in too much oxygen.

“I’m sure I’d love Proust,” he replied, “if my mind was more like the SundarbansThe Sunderbans, a massive jungle straddling the coastal border between Indian and Bangladesh, is most famous as the likely setting Kipling’s The Jungle Book [EDIT: This is a lie! I’ve been telling people this fact for years but it turns out Kipling probably had parts of Madhya Pradesh in mind.] The Sunderbans are also the place where I’ve seen the clearest Milky Way I’ve ever seen. : meandering, all-absorptive, endlessly, er, sub-reticulated. But as it is, Proust makes me weep, weep, weep with boredom. Weep,” he added. He paused and sighed. “Weep, weep, weep,” he continued emphatically. “I weep when I read Proust, and I read very little of him.”

There was a shocked silence: why should anyone feel so strongly about anything? It was broken by Professor Mishra. “Needless to say, many of the most lasting monuments of literature are rather, well, bulky.” He smiled at Amit. “Shakespeare is not merely great but grand, as it were.”

“But only as it were,” said Amit. “He only looks big in bulk. And I have my own way of reducing that bulk,”I so, so, so fervently want to introduce Amit to a Kindle. he confided. “You may have noticed that in a typical Collected Shakespeare all the plays start on the right-hand side. Sometimes, the editors bung a picture in on the left to force them to do so. Well, what I do is to take my pen-knife and slit the whole book up into forty or so fascicles. That way I can roll up Hamlet or Timon — and slip them into my pocket. And when I’m wandering around — in a cemetery, say — I can take them out and read them. It’s easy on the mind and on the wrists. I recommend it to everyone. I read Cymbeline in just that way on the train here; and I never would have otherwise.”All three of Lata’s suitors have affinities for Shakespeare, understandable individually, but cumulatively surprising. Kabir acted in Twelfth Night, and Haresh’s 1951-to-do list was written after ‘‘[it] occurred to him that he was behaving as stupidly as Hamlet.’’

Kabir smiled, Lata burst out laughing, Pran was appalled, Mr Makhijani gaped and Mr Nowrojee looked as if he were about to faint dead away. Amit appeared pleased with the effect.

On memory as plot

I read two novels, novellas really, by Juan Gabriel Vásquez this month — a Colombian novelist with, shall we say, political tendencies. Las reputaciones, or Reputations, stuck with me through two readings, first in English and then Spanish. Vásquez’s plot is fractured and engaging; the narrator is a waning political cartoonist who spends most of his time remembering the future and guessing the past.When people ask me if I can speak Spanish, I usually say yes, but only about things happening right now. Any conjugations beyond the present are beyond me. A singular event drives the action, but that event happened 20 years ago, and is happening now, and will also happen tomorrow. It’s a slow moving disaster, one the narrator calls “the meteorite, always com[ing] from behind,” but really the meteor already impacted.

He combines the metaphor with some shitty, Whorfian anthropology: “For an indigenous tribe in Paraguay, or maybe it was Bolivia, the past is what is in front of us, because we can see it and know it, but the future is what is behind: what we do not see and cannot know. The meteorite always comes from behind, we don’t see it, we can’t see it. You need to see it, see it coming and step aside. You need to face the future. It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards.”

Memory is the key; Vásquez explores the formation of memories, the forgetting of memories, the weaponization of memories, and their anticipation. Anne McLean’s translation is excellent;I enjoyed her translation of Allende’s Maya’s Notebook ages ago. I have no quibbles except the title. Reputations translates directly from Las reputaciones, but reputations (political, sexual, historical) are not what the book is about. Vásquez is interested in legacies,When I chatted to two native speakers about this, they mostly agreed without having read the book. ‘Legado,’ the literal translation of legacy, is much more material in Spanish than English, the primary implication having to do with bequests. and these, not reputations, are the cumulative effect of memories.

In the quote above, I added italics on the last sentence. Vásquez pulls this directly from Chapter 5 of Lewis Caroll’s Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, when Alice is completely perplexed by the retrotemporally-challenged White Queen:

“It’s dreadfully confusing!’

‘That’s the effect of living backwards,’ the Queen said kindly: ‘it always makes one a little giddy at first——’

‘Living backwards!’ Alice repeated in great astonishment. ‘I never heard of such a thing!’

‘––but there’s one great advantage in it, that one’s memory works both ways.’

‘I’m sure mine only works one way,’ Alice remarked. ‘I ca’n’t remember things before they happen.’

‘It’s a poor sort of memory that only works backwards,’ the Queen remarked.”

I had re-readTho I’m not confident I’ve read them them before; I’m just assuming it’s the case. I’d be quite disappointed otherwise!

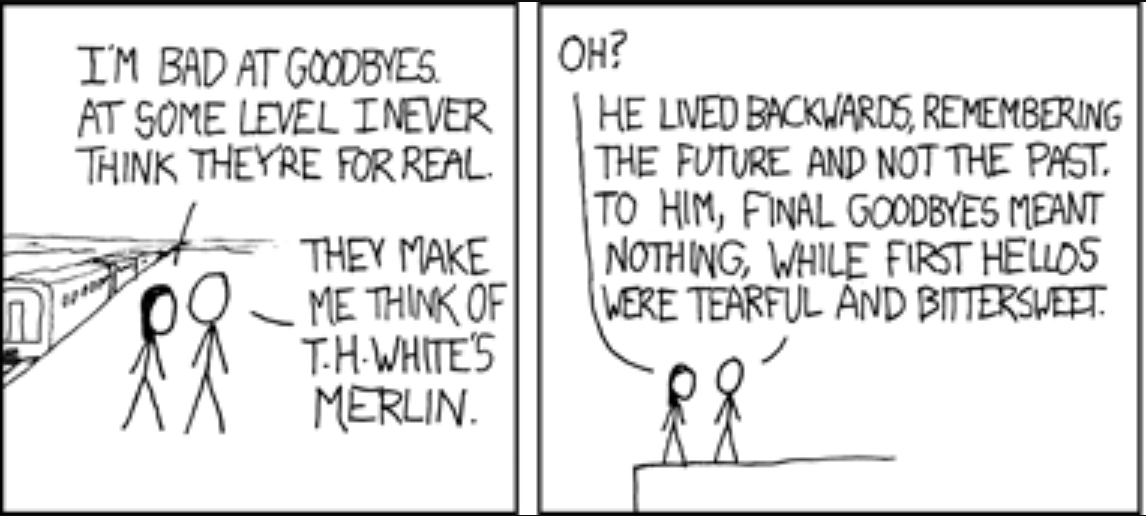

On a day like this, not reading Lewis Caroll next to the Thames seems a waste. both Alice books in early October,At my birthday party in the last weekend of October, my friend Lucy brought me a can of ‘Mad Hatter’s Jabberwocky Jalfrazi,’ without knowing about my recent Alice dive. The best gifts are lucky ones. before I got to Vásquez, so this reference landed with me 90 pages before the narrator’s ex-wife explains the source of the quotation to him in Reputations. The notion of time, of memory flowing backwards is attractive as a plot device and as a psychological mechanism. As a kid, my primary association with the concept was T.H. White’s Merlyn; this was both funnyAnachronistic references to telegraph lines, perplexing Sir Bors, once made me laugh out loud in the Westland Middle School library. and deeply sad.

Surbhi, a friend based in NY, recently gave me a passionate review of Ted Chiang’s short story “Story of Your Life,”The movie Arrival was based on the story. which prompted me to return to my favorite essay in the category “over-the-top sci-fi short story review/physics lesson.” Written, of course, by Gwern, “‘Story Of Your Life’ Is Not A Time-Travel Story” lacks Surbhi’s passion but trumps her on exasperation and rigor. Why do I include it in this section, below Alice and The Once and Future King? Because Gwern’s version of ‘Story’ is about the xenopsychology of memory. In the story, the narrator, a linguist tasked with learning the language of visiting aliens, tells the story from a single point in time about the future and the past. If you enjoyed the story or movie, you’re likely to enjoy Gwern’s review:

Instead, what appears to be precognition in Chiang’s story is actually far more interesting, and a novel twist on psychology and physics: classical physics allows usefully interpreting the laws of physics in both a ‘forward’ way in which events happen step by step, but also a teleological way in which events are simply the unique optimal solution to a set of constraints including the outcome and allows reasoning ‘backwards’. The alien race exemplifies this other, equally valid, possible way of thinking and viewing the universe, and the protagonist learns their way of thinking by studying their language, which requires seeing written characters as a unified gestalt. This holistic view of the universe as an immutable ‘block-universe’, in which events unfold as they must, changes the protagonist’s attitude towards life and the tragic death of her daughter, teaching her in a somewhat Buddhist or Stoic fashion to embrace life in both its ups and downs.

I don’t have much to add, nor the time to condense Gwern’s prose, so please click through if this strikes you as interesting. All of Chiang’s stories are worth perusing.

Elsewhere, I found a delightful short story by Catherynne Valente,I seem to remember it being linked to from the EA Forum, but I can’t imagine in what context. whose wrote a book “about a gaseous moth who devours the memory of love.” “Thirteen Ways of Looking at Space/Time” is written half-autobiographically in the third-person, and half hard sci-fi Bereshit.‘In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God and the Word was a high-density pre-baryogenesis singularity.’ The relevant bits, on Chiangian memory, are in the even-numbered sections:

“Once, someone asked the science fiction writer got her ideas. This is what she said:

… That everything I write is always already written, and that the science fiction writer is sending messages back to me in semaphore, at the speed of my own typing, which is a retroactively constant rate: I cannot type faster than I have already typed. When I type a sentence, or a paragraph, or a page, or a chapter, I am also editing it and copyediting it, and reading it in its first edition, and reading it out loud to a room full of people, or a room with only one or two people in it, depending on terrifying quantum-publishing intersections that the science fiction writer understands but I know nothing about.”

I’ll finish with Le Guin, offering her usual no-nonsense take: “I know who I was, I can tell you who I may have been, but I am, now, only in this line of words I write.”

Other stuff

One weird book was cited in three books I read in late October, frequently enough I had to pay attention.Probably just a Baader-Meinhof coincidence, but a pretty surprising one. The forward to Alice, written by Peter Hunt, concludes that Charles Dodgson was almost surely a pedophile.My metrics professor would deduct points for abusing measure theoretic verbiage here, but ‘almost surely’ and ‘almost everywhere’ have always been counterintuitive phrases. To say that something exists ‘almost everywhere’ in a space both colloquially overstates its frequency — it could not happen infinitely many times on null spaces — and understates it — all of those places have measure zero. Mathematicians need to admit they’re not good at naming things. Hunt writes that “even the most sympathetic of Dodgson’s biographers [find] it necessary to face this particular problem directly (given that his index contains the item, ‘Dodgson, nude female form, attachment to’).” In this discussion, Hunt cites “James Kincaid’s pioneering Child-Loving: The Erotic Child and Victorian Culture,” which writes of the Alice books that they want to “stand on the threshold of … a seduction drama.”

I thought little of this forward, until three days later, when reading Amia Srinivasan’s collection The Right to Sex, I came across a familiar name: “Is there no difference in power between Kincaid, author of Child-Loving: The Erotic Child and Victorian Culture,His research interests are not relevant to Srinivasan’s point — the title of his book is used as a dunk, one which lands quite well. and his student?” Srinivasan, in “On Not Sleeping With Your Students,” takes Kincaid to task for an “abus[ive], pornification” essay on how he interacts with his students. Kincaid’s story is fairly involed,See page 132-136 of the paperback for the receipts, or search for Kincaid’s name. Libgen is a thing. but Srinivasan’s point is that Kincaid is a pedagogical failure: “[his] focus, as a teacher, should be on directing his student’s desire away from himself, and towards its proper object: her epistemic empowerment. If this is what the student wants already, then all Kincaid has to do is exercise some restraint, and not sexualise what is a sincere expression of her desire to learn.”

I recommend the entire collection, and most of Srinivasan’s other writing besides: an essay on bestiality; an obituary of Derek Parfit; an essay on the Rhodes’ legacy. She’s my favorite contemporary feminist philosopher, and my favorite living All Souls Fellow. Three of my friends sat for the All Souls Examination Fellowship this year. While my prior is that none will be elected,Just based on numbers — two fellows are elected annually, from ~400 applicants. All three of my friends are bash-you-over-the-head innovative thinkers who would hold their own in the University’s smallest & most intellectual college. the process sounds delightful. Recent exam questions include “‘O tell me the truth about love’ [W.H. AUDEN];” “Have independent central banks been a failure?;” and “What is special about José Mourinho?” Besides Srinivasan and Parfit, fellows include Lawrence of Arabia,Just went down an rabbit hole of his archaeological work. Anyone, who, at 20 years old, ‘‘cycled 2,200 miles solo through France to the Mediterranean and back researching French castles’’ is owed an interesting life. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,Second president of India. Amartya Sen,I’m so glad I don’t have to deal with social choice theory this year. and Joseph Stiglitz.It’s odd that, of the six All Souls Fellows I listed, I have the fewest opinions about the development economist.

I recently found Zhengdong Wang’s blog, which I place in the same category as my own website, but much better. The highlight is his README page, and the “Maximum Fun” section sourced some fantastic recommendations.Wang also recommends Intepreter of Maladies, which was my absolutely superlative fiction book I read last year, and Memoirs of Hadrian, which was in the top ten. He prompted me to finally watch Knives Out, which did not strike me as superlative, but was very very fun. The recommendation which worked out the best for me (so far), was Jeff Smith’s Bone collection. Wang writes, “It feels like you got through a Lord-of-the-Rings-like experience in one sitting. The art is so sumptuous.” I have never read/watched Lord of the Rings, and this feels like an odd way to get there, but I enjoyed Bone so much that I might try it. Also, Smith’s shades-of-gray style looks beautiful on my extra-large e-ink tablet.

Listening

The Oxford Philharmonic is a delight — it’s a surprise to find a prolific professional orchestra in such a small city. Since March, I’ve seen four of the great symphonies performed by at the Sheldonian Theater, along with five smaller showings. Tchaikovsky’s 5th

The Sheldonian is my favourite non-church designed by Wren, much preferred to the old hall at my semi-alma mater.

The ‘Wren Building,’ on the campus of William & Mary, as depicted by the Bodleian Plate, was probably not even designed by Wren. The concert hall in the Sheldonian is tiny, every seat feels cramped. The D-shaped building is a single room — every wall you can see is an externally-facing wall. And every inch of room is used well.

First, the ceiling mosaic, painted by Robert Streater in 1669 and restored in 2008, is titled “Triumph of Truth and Learning over Envy, Rapine, and Ignorance.” I spent most of Tchaikovsky’s 5th distracted by the ceiling. The main circle consists of anthropomorphized versions of the courses taught at Oxford in the 17th century: Poesy poses with pipes; Mosaical law holds a set of double tablets; Astronomy rests on a giant astrolabethanks, Lucy, for figuring this one out with me ; Chemistry clutches a crucible. On the south side of the ceiling are the titular outcasts: Envy, covered insnakes, falls away from the circle of divine coursework. Rapine and Ignorance, I learned later, are not visible due to the…

…Organ installed in the 1880s, which reaches to the ceiling. While the organ is gorgeous, I was disappointed to learn the beautiful facade is now entirely decorative. From an uncited forum comment:

“The organ was a ‘Father’ Willis of 1877. It was rebuilt by Willis III in 1927/8 to a design of H.P Allen, without any Swell reeds. Harrison & Harrison rebuilt it in 1963 with mutations and a Cromorne on the Choir organ, as was popular at that time.

“The heating baked the organ, so in 1997 one of the Oxford alumni (a QC,) donated a synthetic instrument. It is said that the pipework remains in situ, though the loudspeakers are concealed within the rather splendid T.G. Jackson case.”

I was seated directly under the stage-right proctor’s box

Box for lion-eyed exam proctors. for Brahm’s 1st symphony. I spent most of the intermission speculating with a friend (hi Anna) about the fasces-weilding lions, looking like something out of an Indiana Jones dungeon. The best theory we could come up with is that they are intended to intimidate students sitting their exam in the hall every June.

In mid-June, I returned to the Sheldonian for the Philharmonic’s season closing, a performance of Beethoven’s Choral Fantasy and Choral Symphony, his 9th. Written fifteen years apart, these two pieces are closely related; I’d never heard them side-by-side before. There’s this identical transition from C to E♭All within C major. in the presto of the Fantasy and the climax of the fourth movement of the symphony; the sequence is jarring on it’s own, but startling with the massive build-ups. The Philharmonischer Chor der Stadt Bonn, the choir from Beethoven’s hometown, traveled to Oxford for the concert and blew the roof off the place.

I was excited for this concert for another reason — the pianist for the Choral Fantasy was Marios Papadopoulos, MBE, the music director and conductor of the Oxford Philharmonic Orchestra. My first trip to the Sheldonian, for Tchaikovsky in March, I sat next to the godparents of the concertmaster. This old Jewish couple had traveled up from London for the concert, and boy oh boy did they have gossip about the happenings of the Oxford Phil. Papadopoulos was an especially favored subject — with his shock of white hair and hawkish pout, he is an attractive character out of an Alexander McCall Smith novel. By June, I had spent more than a dozen hours watching Papadopoulos sway on his podium, waving down-beats past his hip with a self-satisfied smile. I was thrilled to watch him play Beethoven, and he seemed to have much more fun conducting while also responsible for the piano.

Most recently, in mid-October, I returned to the Sheldonian for Dvořák’s eighth symphony with my friend Johanna, a German economist. Here, the Sheldonian showed its weaknesses. Even halfway up the seats, the trombones sounded directly in our ears.Tho it is likely trombones have gotten much more powerful over the past century. The eighth symphony sits in an odd place in Dvořák’s life — one can imagine his friends congratulating him after the grandiose, cosmopolitan, brooding seventh symphony in D-minor, then asking him quietly if he’s doing alright. It’s possible he overcorrected - the eighth is downright ebullient. Then came the ninth, the New World, his last. It’s easy to find music historians who claim the seventh as Dvořák’s apogee, and others asserting the New World as unsurpassed. Empirically, the ninth has won; today, it’s played much more often than any other Dvořák symphony. This must be a historical and cultural accident tho — it’s the only great European symphony ever written in Iowa, which makes it enough of a curiosity.

Before each of these performances, I met friends at the White Horse, one of the innumerable 7+-century old pubs scattered around Oxford. The main virtue of the White Horse is it’s proximity to the Sheldonian.

Eating

Lots of baking and large-group meal experimentation this month. Here’s a paragraph about smoothies:

The previous residents of our house, mostly staff at the Center for the Governance of AI, left behind a Magic Bullet. Lack of access to a blender, it turns out, was the only thing keeping me from becoming a smoothie guy. I’ve had smoothies five mornings out of six this month. The staple is a banana at the bottom, frozen blueberries, peanut butter, and chocolate protein powder, but I’ve tossed in apples, oranges, pineapple, mango, avocado, kale, spinach, walnuts, carrots, broccoli, coconut meat, every berry you can imagine, cucumber, yogurt, and chocolate chips.Not all at the same time. Like most eating trends in my life, I don’t expect this to last long, but I’m enjoying the heck out of it in the meanwhile.

Spoiler from above

Amit, needless to say, was disappointed, but not as much as he might have been. His novel, now that he was free from the worry of handling the Chatterji fortunes, was going well, and many more momentous events were taking place on his pages than in his life. He sank deeper into the novel, and — a little disgusted with himself for doing so — used his disappointment and sadness to portray that of a character who happened to be conveniently on hand. […] Perhaps Lata had known that of the three men courting her, the only one who could be rejected without the loss of his friendship was Amit.

Previously

…