What am I up to now?

January 27, 2026

September, 2023

Contents

Updates

I started August in Bonn, on my way to Geneva, and I’m ending the month back in Oxford. Though the school year is still six weeks away, it feels like the home stretch of summer. Besides a trip to The Gambia next month, I’m likely to be in Oxford until the Christmas break.

I was happy to be back in Switzerland. Geneva is less interesting than Bern or any of the small towns I’ve stayed in, but makes up for it with the wonderful variety of license plates. I was there as a mentor for the CHERI fellas, an accomplished and eclectic group of students working on existential risk projects. A supermajority of them were focused on AI, for which I abdicated any mentoring responsibility, but I learned a lot. The fellowship’s research side was superbly organized by Tobias Häberli, a fellow from last year; Tobias was a big help vector to all of this years fellows whom I talked to.

As a fun perk, I got to work closely with a sharp student working on space policy — his “other” mentor being Brian Weeden, at the Secure World Foundation. While I didn’t have as much to contribute, it was really fun dipping my toes back into relevant space topics again, and not the super out-there stuff from the Centre for Space Governance. This project also confused me about all the potential meanings of an “abstain” vote in legislative chambers.

I also got mountains! We stayed under Mt. Blanc for a long weekend and climbed an Alp or two. Besides this, highlights were swimming the Aare again and again, sailing, gelato, and sunrise concerts on the edge of the lake.

My Wonderful Girlfriend (hereafter MWG)She first proposed WC for a proper anonym, after Martha Gelhorn’s use of Unwilling Companion for her less-talented traveling partner in her collection Travels With Myself and Another. We mutually rejected it due to latrinic connotations and it making her sound like a sidekick. left for China at the end of August, where she’ll be for the next year. I plan to head east over the holidays, either to Beijing or a third country — so far, friends are bidding for us to visit Sri Lanka, Singapore, or Bangladesh. Further suggestions are welcome.

Reading

Ethnomathematics

A few months ago, I wrote a bit about Netz’s A New History of Greek Mathematics, in particular his translations of fundamental Greek mathematical concepts.For example, the Greeks’ broadest conception of the word ‘number’ referred to the positive integers excluding 1 — which was not a number, but the unit by which other numbers are measured. This book spun me into a slight enthnomathematical reading spell, which has developed into a middling addiction.

Both the ethnographic (interesting anthropological studies of human interactions with mathematics) and the mathematical (how these interactions are interpreted and decoded mathematically) sides are interesting. This distinction is fine: many human actions can be explained mathematically — by you and me — without the actors having the same knowledge. Paulus Gerdes gives the example of four-fold basket weaving in his wonderful teaching book Geometry from Africa:For images of the basket designs, see section 2.2, ‘From Decorative Designs With Fourfold Symmetry to Pythagoras’, available on LibGen or from me. these designs implicitly reflect the earliest proofs of Pythagoras’s theorem. The weaver follows an inherited artistic and utilitarian tradition, not mathematical calculation. We know what we’re looking for: a larger square of four identical triangles, enclosing a smaller square — the rest of the proof is something I saw in eighth grade. Their practical art bears mathematical reasoning embedded within.

While the geometry is fun (and it’s what captures Netz’s and Gerdes’ curiosity), the original point of curiosity among ethnomathematicians is certainly number theory. This is partly because the first ethnomathematics was conducted by linguists.I will not, I will not, I will not discuss Sapir-Whorf. Distraction! A culture’s number words and base reveal foundational mathematical concepts. That is, if they have number words as we understand them. The Pirahã, an indigenous people in Brazil are an extremely well-studied exampleMy recommendation here is Frank et al.’s Number as a cognitive technology. due to their lack of numbers. Explicitly, they “have no linguistic method whatsoever for expressing exact quantity, not even ‘one’.”

Beside extreme exceptions such as the Pirahã, numbers are almost universal. But even then there is great variety. Our base-10 won out, universal among the Romans and Chinese going back millenia. Base-5 was particularly common in indigenous America; the Babylonian base-60 is the largest common example.

My favorite example is the Yupno of Papua New Guinea.Sources here are Wassman and Dasen 1994 and Wassman 1991. We don’t know much about their mathematics, and my fascination with them is inherently a bit speculative. First, they were only studied ethnographically decades after the national government began providing languageTok Pisin. and mathematical schooling to the region. Only the oldest members of the are familiar with their counting system; children “usually know only the vernacular words for 1, 2, and 3; they usually count in Tok Pisin even when they use the vernacular.” Second, the authors had only limited access to the Yupno community. My claim about the Yupno — which the authors imply, but do not state — is that their men count in base 33 and women count in base 30.

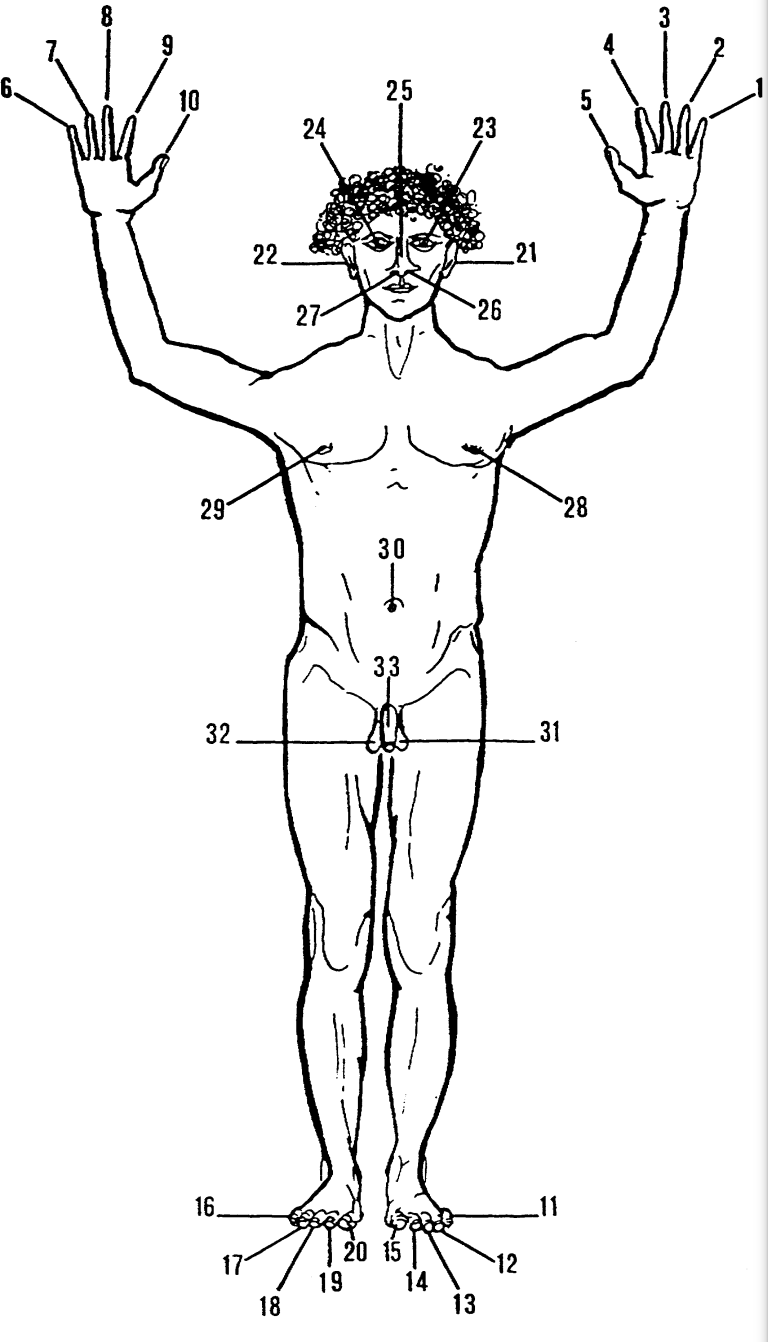

The Yupno use a body-tally number system. This is similar to how most base-10 systems, what we’re used to, came about: you start at one finger, and move to the next until you get to ten. Then start over. But the Yupno observe that there are more body parts than just fingers. Wassman provides this diagram:

The problem, I think, is obvious.Proofreader LH asks whether this implies that ‘‘the vagina is the absence of a body part.’’ Definitely, yes. Anthropologists have, by varying degrees, addressed or ignored anthrocentrism. Sally Slocum has a few fun papers, of which I’ve read one, years ago.

However, we don’t have any direct evidence for the claim of gendered base systems. The authors’ “sample does not include any women because tradition does not allow them to count in public; attempts to question some of them in spite of this failed because the situation was too strange for them.” Further, it was rare for the Yupno to deal with numbers larger than 30, and therefore the practical difference is often irrelevant.Base only becomes relevant mathematically once the base is exceeded. In a base-11 system, our 11 and their 11 are the same, but our 12 is equivalent to their eleventy-one or whatever. Of course, you can call eleventy-one ‘twelve’ but then you’re in a baseless linguistic system and being purposefully obtuse so stop it. The primary example is the payment of bride prices, which is also notable for being the only occasion when men and women count together. Wassman again:

Occasions to go beyond two or three menWhen the Yupno men reached 33, they would pick another man present and count using his body parts. would have been rare; traditionally, higher numbers were only used in the exchange of bride price, and even then it would have been unusual to count more than 33 pigs.

That’s the outline of how the Yupno ended up with a gendered base system. When I tried to think about mathematics in the Yupno system, it was clunky for reasons beyond the unfamiliarity. The important question, I think, and this is the closest I’m getting to Sapir-Whorf, is this: would a Yupno Ramanjuan have been possible?

The Shadow of the Sun

My favorite book from this month was The Shadow of the Sun by Ryszard Kapuściński. Almost no one traveled as widely in Africa as Kapuściński, a (the) Polish journalist covering the third world from the ~1960s to the ~1990s.This is quite a claim but I challenge you to find post-colonial travelers with such a spread. Kapuściński doesn’t mention South Africa, and neglects Egypt and Libya, but there are no other unvisited African regions in the 150 page book. Kapuściński’s journalism is not consistent; he is often torn between covering the sigular events of decolonization and describing the quotidian lives of the people he meets. Highlights include bouts of malaria and tuberculosis; an explosively written battle with a cobra; intense cross-desert logistics; unexpected churches of every variety; coups, revolutions, elections, and wars; and endless sweating.

Kapuściński’s lecture on the Rwandan genocide, given shortly after, placed the tragedy firmly in time and place. While taking place in a small, isolatedKapuściński claims the first European entered Rwanda in 1894. I have not googled. country, the genocide was a regional phenomena. Refugees scattered far; Tutsi fighters were trained in Uganda; the conflicts of the DRC are — to this day — worsened on by both Tutsis and Hutus based in Rwanda. In time, while the 100 days in 1994 are what we know, massacres of comparablePossibly comparable size. As Kapuściński writes, ‘‘Many wars in Africa are waged without witnesses, secretively, in unreachable places, in silence, without the world’s knowledge, or even the slightest attention.’’ size occurred in 1959, 1963, 1972, 1986, and 1990. 1994 was just the climax of a centuries long struggle following the upset of the status quo by decolonization.

Kapuściński indicts the colonial powers, both for creating the conditions leading to the decades of blood and recrimination and for the 1994 explosion itself. In the 50s, among the European countries, Belgium was uniquely unprepared for decolonization.

Until now, the Belgians ruled Rwanda through the Tutsis, leaning on them and using them. But the Tutsis are the most educated and ambitious sector of the Banyarwanda, and it is they who now are demanding freedom. And they want it immediately, something for which the Belgians are utterly unprepared. So Brussels abruptly switches tactics: it abandons the Tutsis and begins to support the more submissive, docile Hutus. It begins to incite them against the Tutsis. These politics rapidly bear fruit. The emboldened, encouraged Hutus take up arms. A peasant revolt erupts in Rwanda in 1959. […] A great massacre began, such as Africa had not seen for a long time. The peasants set fire to the households of their lords, slit their throats, and crushed their skulls. Rwanda flowed with blood, stood in flames.

The Belgians washed their hands of Africa as well as they could. The French have done the opposite. Without their intervention in 1990, “maybe it would never have come to that hecatomb and carnage—the genocide of 1994.”

Whereas the majority of European capitals had radically broken with their colonial past, Paris had not.I remain upset at French policy in Africa. Across the Sahel, and further south, they have started and worsened conflicts which kill hundreds every day. I notice I’m being vague here, but I am referring to events much more recent than Rwanda. Who was the first head of state with their arm around Chadian ‘‘Transitional’’ President Mahamat Deby? You get one guess. [… In 1990,] The divisions of the Rwandan Patriotic Front were already closing in on the capital, and Habyarimana’s government and clan were packing their bags, when airplanes deposited French paratroopers at the airport in Kigali.

All of this is in a lecture rich with historical contextI vaguely remembered Kapuściński’s version of Fashoda from my high school history class, another of those fascinating and forgotten almost-wars. and visual imagery:

The image of the [mountainous fortress of Rwanda] is not poetic license. Whether you enter Rwanda from Uganda, Tanzania, or Zaire, you will always have the same impression of stepping through the gates of a stronghold that rises up before you, fashioned from immense, magnificent mountains. And so it is now for the Tutsi, a freshly exiled and homeless vagabond; when he awakens in the morning in a refugee camp and walks out in front of his shabby tent, he beholds the mountains of Rwanda. In those early hours of the day, they are a startlingly beautiful sight. I myself often jumped up at dawn just to look. High yet gentle peaks stretch before you into infinity. They are emerald, violet, green, and drenched in sunlight. It is a landscape devoid of the dread and darkness of rocky, windswept peaks, precipices, and cliffs; no deadly avalanches, falling rocks, or loose rubble are lying in wait for you here. No. The mountains of Rwanda radiate warmth and benevolence, tempt with beauty and silence, a crystal clear, windless air, the peace and exquisiteness of their lines and shapes. In the mornings, a transparent haze suffuses the green valleys. It is like a bright veil, airy, light and glimmering in the sun, through which are softly visible the eucalyptus and banana trees, and the people working in the fields

Did Kapuściński understand Africa? He generalizes often — “Africans apprehend time differently;” “Africans valued and liked to make contact on the higher, spiritual plane;” “Africans are collectivist by nature” — and some fall flat. His interactions with individuals shine the brightest. The most touching was with a driver in Nigeria, Omenka.

On the day we first met, I gave him nothing as we parted. He walked away without so much as a good-bye. I dislike cold, formal relations between people and I felt bad. So the next time I gave him 50 naira (the local currency). He said good-bye, and even smiled. Encouraged, I gave him 100 naira the following time. He said good-bye, smiled, and shook my hand. At the subsequent parting, I gave him 150 naira. He said good-bye, smiled, wished me well, and warmly shook my hand, grasping it in both of his. The next time I raised the rate again and paid him 200 naira. He said good-bye, smiled, shook and squeezed my hand, asked me to pay his respects to my family, and with concern in his voice inquired after my health. Without stretching this story out any longer, suffice it to say that I ended up showering him with so many naira that we were simply unable to part. Omenka’s voice was always trembling with emotion, and with tears in his eyes he would swear his everlasting devotion and fidelity.

I had what I wanted, and more: tenderness, warmth, goodwill.

This is what I found the hardest about Sierra Leone. Genuine relationships are possible — but they can only be bought. The transactional is at the center of every interaction. It is not always economic — attention, promises, presence, gifts, or information are easily exchanged — but, as a white man, the economic is expected. Kapuściński looks back at his earliest, most naive efforts to relate to Africans, and recognizes them for what they were.

In their eyes, I was guilty. Slavery, colonialism, five hundred years of injustice—after all, it’s the white men’s doing. The white men’s. Therefore mine. Mine? I was not able to conjure within myself that cleansing, liberating emotion—guilt; to show contrition; to apologize. On the contrary! From the start, I tried to counterattack: „You were colonized? We, Poles, were also! For one hundred and thirty years we were the colony of three foreign powers. White ones, too.” They laughed, tapped their foreheads, walked away. I angered them, because they thought I wanted to deceive them. I knew that despite my inner certainty about my own innocence, to them I was guilty.

I’ll end with a story from Grant Gordon, a former UNDPO and IRC officer. When he was in Rwanda, he told a local coworker about his grandparents, three of whom were Holocaust survivors. Later, when she introduced Gordon to her husband, she introduced him as a “brother in genocide.” No morals here (people are different); I just thought of these two stories together.

Music

Good stuff from this month:

- Tongues — Amy Denio

- Inde de Sud — Lakshminarayana Subramaniam

- Say So — Bent Knee

- Loveless — My Bloody Valentine

- Danzon — Turtle Island String Quartet

- Marry Me — St. Vincent

- Dizzy Gillespie at Newport — Dizzy Gillespie

This post was written with the Grateful Dead’s “Bertha” from Skull and RosesThe eponymous album cover was based on an illustration from a Victorian-era edition of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam ! The illustration was apparently on the same page as this poem. on repeat.

Previously

…